Gut Microbiome and IBD

Key points

- The gut microbiome includes hundreds of different species of microbes that live in the gastrointestinal tract

- There are both beneficial and potentially harmful microbes in the gut. It’s important to have a healthy balance to support the immune system

- A healthy diet and active lifestyle can support a healthy gut microbiome

- Treatments that directly target the gut microbiome are still being actively researched e.g., faecal microbiota transplant

What is the microbiome and why is it important?

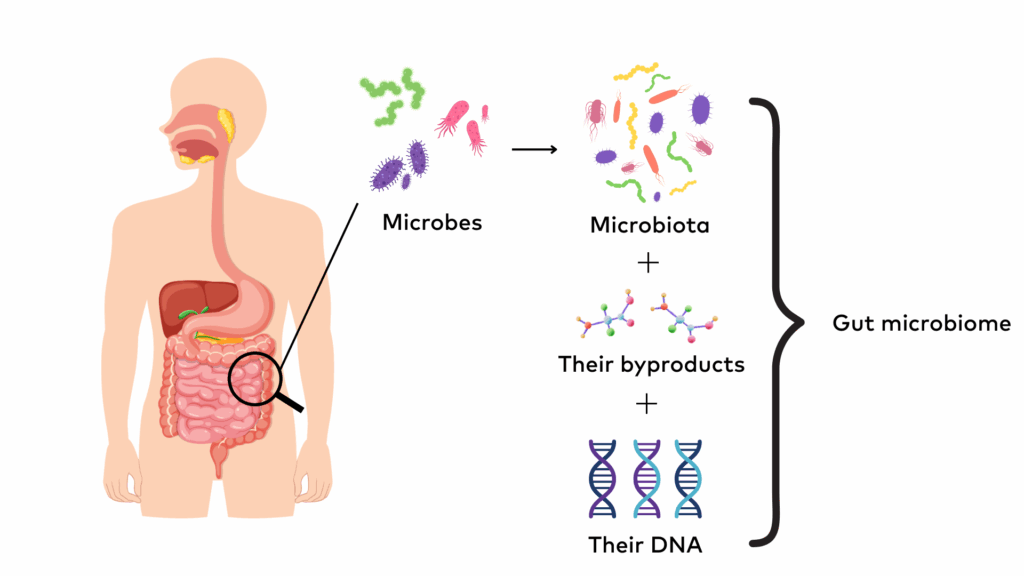

The microbiome is a collective term that refers to the community of all microbes (e.g. bacteria, fungi) that naturally live on and inside the human body. It also encompasses the genetic material of the microbes (i.e., their DNA) and the byproducts they produce (e.g., short-chain fatty acids). The human microbiome has many different types of microbes which means it is ‘diverse’. Each person’s microbiome is unique to them. Different parts of the body (e.g. the gut, tongue, skin) have different groups (colonies) of microbes living in or on them and are collectively known as the microbiota for that body part. There are trillions of bacteria, viruses, and fungi making up the human microbiota, and the gut is the most populated and diverse.

The gut microbiome includes hundreds of different species of microbes that live in the gastrointestinal tract, mainly in the large intestine (colon). The gut microbiome can change in response to diet, medications, illness, and other lifestyle factors. The number and balance of microbes in the gut can even change from meal to meal. Many of the microbes are beneficial for our health and work together to support our health. In the gut, microbes are responsible for:

- Helping to digest food and absorb nutrients

- Regulating the immune system

- Protecting against harmful (pathogenic) microbes (e.g. viruses)

- Producing compounds that are essential to our health, like various B vitamins, vitamin K, and short-chain fatty acids.

There are both beneficial (‘good’) and potentially harmful (‘bad’) microbes in the gut which can negatively affect our health. Having many different microbial species is important to maintain good health.

What is the connection between the gut microbiome and IBD?

Multiple causes of IBD have been suggested based on genetic risk, environmental factors, and more recently, the gut microbiome. The gut microbes can affect people respond to specific drugs, impacting how effective they are. This may be involved in how people respond to biologics. However, we are only just beginning to understand the extent of the impact of the microbiome in our health and more research is needed.

People living with IBD typically have less diversity in their gut microbiome. It’s possible that this is because of inflammation caused by the disease. Normally, the gut is a low oxygen (anaerobic) environment. This environment supports a wide range of microbes that thrive without oxygen and prevents oxygen-tolerant microbes from taking over. This ensures there is a delicate and healthy balance of microbiota that are resilient to harmful pathogens.

However, when the gut is inflamed (such as in an IBD flare up), immune cell activity and tissue damage cause oxygen levels in the gut to increase. This oxygen-rich environment allows oxygen-tolerant microbes to grow and multiply, creating an imbalance of microbes. This imbalance, known as dysbiosis, can make inflammation worse and reduce the gut’s ability to fight off invasions from harmful microbes.

Another cause of dysbiosis for people living with IBD is related to the intestinal lining (mucosa). The intestinal lining normally acts as a protective wall, keeping bacteria and other harmful substances from entering deeper layers of the gut. However, people living with IBD can often have inflammation that damages the intestinal lining. When the lining becomes inflamed, its barrier function is impaired, and harmful bacteria can cross into the deeper gut tissue. The harmful bacteria trigger an inflammatory immune response, making it harder for the intestinal lining to heal and starting a chronic cycle: inflammation damages the barrier, and the damaged barrier leads to more inflammation.

The result of barrier damage and dysbiosis is a chronic inflammatory cycle that is hard to get under control. It’s unclear if dysbiosis is a cause or consequence of the inflammation in IBD, it’s most likely a bit of both.

What impacts the gut microbiome?

The gut microbiota begins to form at birth and is mostly established during the first 3 years of life. During a vaginal birth, babies are exposed to bacteria from the mother’s vaginal canal and gut which helps to create the newborn’s microbiome. Babies born via caesarean section are typically exposed to skin and environmental bacteria instead, creating a different microbiome from a baby born vaginally. Breastfeeding can also assist a baby’s microbiome to grow through providing beneficial bacteria and nutrients that feed healthy microbes. In addition, being exposed to different bacteria in the first years of life through diet and the environment helps to populate the microbiome.

In adulthood, the gut microbiome becomes relatively stable but can still shift in response to changes in diet, lifestyle, medications, and disease. An imbalance in the gut microbiota has been linked to, but not necessarily the cause of, many chronic diseases such as IBD, asthma, cardiovascular disease, metabolic disorders (e.g. obesity), mental health conditions (e.g. anxiety) and autoimmune disorders (e.g. type 1 diabetes). Several factors can influence the balance of microbes in the gut:

- Medication. Medication such as antibiotics can disrupt the balance of gut bacteria. Antibiotics are designed to kill harmful bacteria but are not selective, and therefore also kill the good bacteria that are important for our health. This can lead to reduced diversity. A healthy gut will recover within a few months, but prolonged or repeated use can lead to problems like clostridium difficile infection or antibiotic resistance. Other medications like painkillers, sleeping pills, and antidepressants can also cause changes to the gut microbiome.

- Diet. The Western diet which consists of ultra-processed foods and drinks that are high in energy, saturated fat, and sugar, and low in fibre, can disrupt the delicate balance of the gut microbiome and promote inflammation.

- Lifestyle factors. Smoking, alcohol consumption, chronic stress, and lack of sleep and physical activity can negatively impact the gut microbiota composition.

Some companies advertise at-home microbiome stool tests that provide a report of the different microbiota in your gut. You should be cautious buying a test yourself online, as it may not be evidence-based or scientifically validated. These tests are typically expensive and could cost you hundreds of dollars. The tests only show your gut at one point in time. As there are so many factors affecting the gut microbiome, the composition may have changed by the time you get your results back. There are also privacy concerns about how your sensitive health data is stored or who might be able to access the information. If you’re considering a stool test, it’s best to talk to your doctor or a qualified health professional first.

How can I keep my gut microbiome healthy?

Consuming a healthy diet is one of the most important ways to keep your microbiome healthy. Gut microbes use nutrients from your diet to grow and carry out functions that support your health.

Eating a large variety of plant-based foods each week is essential to support a diverse range of microbes to grow in the gut that are resilient to harmful bacteria. A high fibre diet (25-30g a day) helps the growth of good bacteria in the gut and reduces the risk of constipation, bowel cancer, and other diseases. Fibre is a type of carbohydrate that is abundantly found in whole grains, fruit, vegetables, legumes (e.g., lentils), nuts, and seeds.

Dietary fibres cannot be digested by our bodies and pass through the digestive tract largely intact. Some fibres, known as prebiotics, are broken down by beneficial gut microbes, which use it as fuel for their growth and activity. This process produces beneficial products like short-chain fatty acids, which help to reduce inflammation, strengthen the gut lining, and support immune function.

Foods rich in prebiotic fibres include:

- Fruit and vegetables like garlic, onion, leek, asparagus, and under-ripe bananas

- Wholegrains like wheat, oats, and barley

- Legumes like beans, lentils, and chickpeas.

You can also support your gut health by consuming probiotic foods, which contain live beneficial microbes. They are often referred to as good bacteria because they may help restore or maintain a healthy balance of microbes in the gut. Natural sources of probiotics include:

- Fermented dairy such as yoghurt with live cultures and kefir

- Fermented vegetables such as sauerkraut

- Fermented soy products such as tempeh and miso.

Learn more about Nutrition for IBD.

Microbiome treatments being researched for IBD

Treatments that target the gut microbiome are still being actively researched for IBD. While some early research studies show promise, these treatments are still experimental and not part of the standard care for IBD. They may not be effective for everyone, and you should always speak to your healthcare team before starting any new treatments or making changes to your healthcare plan.

1. Faecal microbiota transplant

What is faecal microbiota transplant?

Faecal microbiota transplant (FMT), also known as a stool (poo) transplant, is an emerging treatment that is being explored for IBD, particularly ulcerative colitis. FMT works by extracting the beneficial bacteria from the stool of a healthy donor and transplanting it into the colon of someone with disease.

The aim of FMT is to create a new composition in the gut microbiome of the person with disease, typically increasing the number and diversity of bacterial strains. In theory, this can help to establish a healthy immune response, reduce gut inflammation, and heal the intestinal lining.

The microbes from the faecal transplant can be administered in two ways:

- The rectal route, which uses enemas or colonoscopies. In this route, the faecal preparation is inserted into the colon. Colonoscopy is the most common method for FMT and requires bowel preparation beforehand.

- The oral route, which uses capsules that can be swallowed or nasogastric tubes. If using a nasogastric tube, the tube is inserted into the nose and the faecal preparation is sent through the tube to the intestines.

Currently FMT is accepted and recommended as a treatment for recurrent or severe Clostridioides difficile (C.difficile) infection. C.difficile is a bad bacteria in the gut that can overtake the good bacteria, typically after using antibiotics. C.difficile infection causes fever, diarrhoea, and cramping and can have severe health impacts, especially for older people. FMT has been very effective as a treatment to resolve C.difficile infections.

Some emerging evidence about FMT indicates that it has been effective for inducing remission in people with active ulcerative colitis. However, more evidence is needed before it can be recommended and accepted as an IBD therapy. There is minimal evidence for treating Crohn’s disease. There is very limited availability of FMT and it’s not a widely performed treatment in Australia. FMT for IBD treatment should only be conducted in a clinical trial setting until more evidence is documented and it’s accepted as an evidence-based maintenance therapy.

There are still major challenges before FMT can progress to an approved treatment for IBD, including working out the ideal composition, formulation, induction, and maintenance doses. There’s also evidence needed to understand its safety and who could benefit the most from these treatments.

What are the risks of FMT?

FMT is still an experimental treatment for IBD and there is more to learn about the risks. Minor side effects are usually gastrointestinal, like abdominal cramps, diarrhoea, or constipation, and resolve within a week of transplantation. If you receive the faecal transplant through colonoscopy, there are risks of infection, bleeding, tearing, or bowel perforation. There is a very small risk that a faecal transplant could transfer a harmful pathogen (e.g. a virus) to the person receiving the donor’s stool.

The long-term risks are not fully understood because most studies have been published in the last decade. It’s also not well documented about how FMT may affect other body systems. Given how much research is being published about the gut microbiome’s connection to other body systems (e.g. through the brain-gut connection), research needs to be done into the impact of FMT in areas such as mental health.

2. Prebiotics, probiotics, and postbiotics

Prebiotics, probiotics, and postbiotics are closely linked components of the gut microbiome ecosystem. All of these can be supplemented to alter the health of the gut. However, research is still ongoing about whether they can improve IBD symptoms and alter disease progression.

- Prebiotics. Prebiotics can be taken as a supplement or consumed from the diet. In general, prebiotics are very important for gut health. However, clinical evidence of the impact of prebiotic supplementation in IBD patients is limited and more research is needed. In some cases, prebiotics may worsen gut symptoms, though this may be due to other contributing factors rather than the prebiotics themselves. If prebiotic intolerance is suspected, it’s best to consult an Accredited Practising Dietitian with expertise in gastroenterology or IBD before removing them from the diet.

- Probiotics. Probiotics are commonly consumed through the diet but can also be taken as a supplement. The probiotic supplement will specify on the label which strain of probiotics it contains. Not all strains provide the same benefits for each person and a product with a larger dose or more strains is not always better. Not all probiotic products on the market contain high-quality ingredients that will benefit the gut and stay alive during long-term storage. Probiotic supplements typically pass through the gut rather than colonise, but they can still interact with the resident microbes to support digestive health. There has been some preliminary evidence to suggest that certain probiotic supplements could be helpful for pouchitis and ulcerative colitis. However, more evidence is needed in this area, and you should speak to your IBD team for specific advice related to your needs.

- Postbiotics. Postbiotics are products of bacteria and other components of the microbiome. These include compounds such as short-chain fatty acids, organic acids, proteins, and vitamins. Postbiotics are currently being researched as a new IBD therapy for their potential in maintaining the health of the intestinal lining and immune function. It is hoped that postbiotics could correct the impact of gut dysbiosis (i.e. imbalanced gut microbiota) by reducing inflammation and helping digestive symptoms. There is a lot of research needed to understand the potential for postbiotics to improve IBD symptoms before the treatment progresses.

While our understanding of the gut microbiome and its role in IBD is still evolving, it’s clear that having a diverse and balanced gut microbiome is important for overall health. A healthier diet and lifestyle can support a healthy microbiome, but treatments that directly target it, such as FMT or supplements, are still being actively researched. Always consult your healthcare team before making changes to your treatment or trying new therapies.